|

||||||

History:

Pre-dynastic history

|

Archaeological evidence suggests that hunters inhabited Egypt over 250,000 years ago when the region was green grassland. The Paleolithic period around 25,000BC brought climatic changes, which turned Egypt into a desert. The inhabitants survived by hunting and fishing and through a primitive form of cultivation. Desertification of Egypt was halted by rains, which allowed communities of cultivators to settle in Middle Egypt and the Nile Delta. These farmers grew wheat, flax and wove linen fabrics in addition to tending flocks.

The first indigenous civilizations in Egypt

have been identified in the south of the country through archaeological

excavations. The Badarian culture is the earliest known developed Egyptian

civilization based on farming, hunting and mining. Badarians produced fine

pottery and carved objects as well as acquiring turquoise and wood through

trading.

The Naqada lived in larger settlements about

4,000BC and produced decorated pottery and figurines made from clay and

ivory, which indicate they were a war-like people. Naqada artifacts from

3,300BC show further development both in terms of culture and technology.

Evidence of irrigation systems and more advanced burial sites, as well as

the use of alien materials like lapis lazuli, indicate a cultural diversity

and the development of external trading.

|

|

| Throughout

most of its pre-dynastic history Egypt encompassed a multiplicity of

settlements, which gradually became small tribal kingdoms. These kingdoms

evolved into two loosely confederated states; one encompassed the Nile

valley up to the Delta (with the Naqada dominating) with Hierakonpolis as

capital, represented by the deities Seth and White Crown; the other

encompassed the Delta, with Buto as its capital and represented by the

deities Horus and Red Crown.

The two kingdoms vied for power over all the land of Egypt. This struggle led to the victory of the south and the unification of the Two Lands in 3100BC under the command of Menes who is also known as Narmer. This was the beginning of the dynastic period of the Pharaohs. |

The Early Dynastic or

Archaic Period (3100-2686BC)

This period is shrouded in mythology. Little is

known of Menes and his descendants outside of their divine ancestry and that

they developed a complex social system, patronized the arts and constructed

temples and many public buildings.

| The

foundation of Memphis, the world's first imperial city, is attributed to

Menes. From Memphis the third and fifth kings of the First Dynasty, which

extended from 3100 to 2890BC set out to conquer the Sinai. During the First

Dynasty culture became increasingly refined. The royal burial grounds at

Saqqara and Abydos became sites of highly developed mastabas.

The Second Dynasty

lasting from 2980 to 2686BC was characterized by regional disputes and a

decentralization of Paranoiac authority, a process that was only temporarily

halted by the Pharaoh Raneb, also called These regional

contentions were very likely the outcome of the unresolved conflict between

the two deities Horus in the south and Seth in the Delta. Theistic rivalry

seems to have been resolved by Khasekhem, the last Pharaoh of the Second

Dynasty |

|

The Old Kingdom

(2686-2181BC)

| Paranoiac

burial practices continued to develop during the Third Dynasty, lasting from

2686-2613BC, which marked the beginnings of the Old Kingdom. The first of

Egypt's pyramids were constructed during the 27th century BC. The Step

Pyramid of Saqqara built for King Zoser by his chief architect Imhotep, who

later generations deified, is considered by many to be the first pyramid

ever constructed in Egypt.

Prior to this, most royal tombs were constructed of sun-dried bricks. Zoser's gargantuan step pyramid attested to the pharaoh's power and established the pyramid as the pre-eminent Paranoiac burial structure. During Zoser's rule the Sun God Ra attained a supra-eminent place over all other Egyptian deities. |

|

The Fourth Dynasty (2613-2494BC) was characterized by expansionism and pyramid construction. King Sneferu constructed the Red Pyramid at Dahshur near Saqqara and the Pyramid of Meidum in Al-Fayoum.

| He also

sent military expeditions as far as Libya and Nubia. During his reign

trading along the Nile flourished. Sneferu's descendants, Cheops (Khufu),

Chephren (Khafre) and Mycerinus (Menkaure) were the last three kings of the

Fourth Dynasty. These three pharaohs built the pyramids of Giza.

Egypt under Cheops became the first state in

the history of the world to be governed according to an organized system.

The Fourth Dynasty also extended trade relations with the Near East and

mined and smelted copper in Nubia.

|

|

The Fifth Dynasty (2490-2330BC) was marked by a

relative decline in Paranoiac power and wealth, evidenced by the smaller

pyramids of Abu Sir built during this period. The pharaohs ceased to be absolute

monarchs and began to share power with the aristocracy and high officials. As

the independence of the nobility increased, their tombs became larger and were

built at increasing distances from the pharaohs.

Worship of the sun god Ra also spread during the

Fifth Dynasty. It was during the reign of Unas that religious texts were placed

in the pyramids bearing descriptions of the afterworld, which were later

gathered into the Book of the Dead.

Decentralization of

Paranoiac authority increased during the Sixth Dynasty (2330-2170BC) as small

provincial principalities emerged to challenge Paranoiac power. The Sixth

Dynasty kings were forced to send expeditions as far as Nubia, Libya and

Palestine to put down the separatists, but these campaigns served to further

erode the central authority. By the reign of the last Sixth Dynasty Pharaoh Pepi

II, the Old Kingdom had become a spent force.

|

The First Intermediate

Period (2181-2050BC)

Out of the turmoil and Paranoiac inertia,

principalities within the realm raised up to challenge the authority of the

kings. Achthoes, ruler of Heracleopolis, seized control of Middle Egypt,

seized the throne and founded the Ninth Dynasty (2160-2130BC).

The kings of Heracleopolis maintained control over northern Egypt through the Tenth Dynasty (2130-2040BC). However, the rulers of Edfu and Thebes fought over control of Upper Egypt. Thebes won the battle over Upper Egypt and its ruler Inyotef Sehertowy founded the Eleventh Dynasty (2133-1991BC) with the aim of extending his power over all the land. The north-south battle for control of Egypt

ended with the victory of Nebhepetre Mentuhope II who reunited the country

under one king and launched the Middle Kingdom. |

|

|

The Second Intermediate

Period (1786-1567BC)

The Thirteenth and Fourteenth Dynasties were

powerless to put

down the Hyskos, tribal warlords with foreign support who seized control of the Delta, establishing the capital of Avaris and moving south. Despite their alien origins (Hyskos means "Princes of Foreign Lands") and foreign ties, the Hyskos assumed an Egyptian identity and ruled as pharaohs. The Hyskos dominion was shaken by Thebes,

which established the Seventeenth Dynasty and, under Wadikheperre Kamose,

laid siege to Avaris. When his successor Ahmosis expelled the Hyskos from

Egypt in 1567BC, the New Kingdom was born. |

|

|

The New Kingdom

(1567-1085BC)

Ahmosis founded the Eighteenth Dynasty

(1567-1320BC), which reigned over the first part of a prosperous and stable

imperial period during which Paranoiac culture flowered and Egypt became a

world power.

During the Eighteenth Dynasty Nubia was subdued

and its wealth of gold, ivory, gemstones and ebony flowed into Egypt.

Paranoiac armies conquered the Near East, Syria and Palestine and workers

from these new-established colonies, and a cultural cross-fertilization took

place as artisans and intellectuals transplanted their knowledge, skills and

culture onto Egyptian soil.

The temple of Karnak at Thebes grew with the expansion of empire. Tuthmosis I constructed the first tomb in the Valley of the Kings. His daughter reigned as pharaoh and built the temple of Deir Al-Bahri. Tuthmosis III expanded the empire beyond Nubia and across the Euphrates to the boundaries of the Hittites. Imperial expansion continued under Amenophis

II and Tuthmosis IV. The reign of Amenophis III was the pinnacle of Egyptian

Paranoiac power. Under Amenophis III the kingdom was secure enough for the

Pharaoh to build many of the greatest Paranoiac structures including the

Temple of Luxor.

|

|

His son Amenophis IV fought with the priesthood of

the god Amun and changed his name to Akhenaten in honor of the god Aten. With

his wife Nefertiti Akhenaten he established a new capital at Tel El-Amarna

dedicated to the worship of Aten, which many believe was the first organized

monotheistic religion. Both his predecessors and successors denounced his

beliefs as heresy.

During their short reign (1379-1362BC) Paranoiac

obsession with the afterlife was banished, as was the old idolatry. Art began to

reflect human concerns. This was called the Amarna revolution, which barely

survived

Akhenaten's reign. His successor Smenkhkare upheld

Akhenaten's ideals but died within a year, leaving the child pharaoh Tutankhamen

under the influence of the priesthood who easily convinced him to renounce the

monotheism of his father-in-law and return to rule from Thebes.

This period has been called the Theban

counter-revolution during which time the priesthood destroyed any traces of

Akhenaten's reign, including the Temple of the Sun at Karnak.

Tutankhamen ruled for nine years until just before

reaching manhood, when he died. He is most remembered in modern times for the

fabulous and pristine treasures uncovered when his tomb was discovered in 1922.

Ay and Horemheb, the last Eighteenth Dynasty kings, both of whom worked to eradicate Akhenaten’s revolutionary beliefs and restore the status quo, succeeded Tutankhamen.

|

The Nineteenth Dynasty

(1320-1200BC)

Was established by the Horemheb's wazir, or

minister, Ramses I who reigned for two years. Ramses and his descendants

were warrior kings who recaptured territories lost under Akhenaten. His

successor Seti I regained controls over Egypt's eastern colonies in

Palestine, Nubia and the Near East. Seti I also began construction on a

majestic temple at Abydos, which was completed by his son Ramses II who

reconquered Asia Minor.

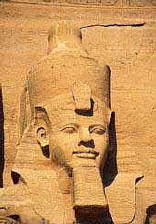

Ramses also constructed monumental structures

like the Ramesseum in Thebes and the sun temples of Abu Simbel. His son

Merneptah spent much of his reign driving back invaders from Libya and the

Mediterranean but he is believed to be the biblical Pharaoh described in

Exodus. Seti II was the last king of the Nineteenth Dynasty.

The Twentieth Dynasty (1200-1085BC) was to be the last of the New Kingdom and was first established by Sethnakhte. By the reign of his successor Ramses III, the kingdom was occupied with defending itself against Libyan and "Sea People" invasions. Ramses III constructed the enormous palace temple of Medinet Hebu but the empire had begun to disintegrate with strikes, assassination attempts and provincial unrest. His successors, who were all named Ramses,

presided over the decline of their empire until Ramses XI withdrew from

active control over his kingdom, delegating authority over Upper Egypt to

his high priest of Amun, Herihor, and of Lower Egypt to his minister Smendes.

These two rulers were the last of the New Kingdom. |

|

The Late Period (1085-322BC)

The Twenty-First Dynasty was established by

successors of Herihor and Smendes who continued to rule Upper and Lower Egypt

separately from Thebes and Tanis. But by this period external threats from

Libyan invaders and others were eroding Egypt's power to defend itself.

Eventually both Upper and Lower Egypt succumbed to foreign invasions. Libyan

warriors who established their own Twenty-Second Dynasty drove the Tanites from

power.

Upper Egypt held out longer against Nubian invaders

until being overrun by the armies of their ruler Piankhi all the way to Memphis.

Piankhi's brother Shabaka marched north to conquer the Delta and reunite Upper

and Lower Egypt under the Twenty-Fifth Dynasty of Nubian Kings (747-656BC).

During this period there was an artistic and cultural revival. The Twenty-Fifth

Dynasty ended when Assyrian armies captured Memphis and attacked Thebes, driving

the Nubian pharaoh Tanutamun back to Nubia.

The Assyrians found a willing Egyptian collaborator

in the form of a prince from the Delta. Psammetichus I governed on behalf of the

Assyrians until they were forced to withdraw their forces to wage war against

the Persian Empire. On the departure of the Assyrians, Psammetichus I declared

himself pharaoh and established the Twenty-Sixth Dynasty, ruling over a

re-united Egypt from his capital at Saïs in the Delta. This was to be the last

great Paranoiac age, which witnessed the revival of majestic art and

architecture and the introduction of new technologies.

|

Gradually, though, the power of the kingdom was eroded

through invasion, ending ignominiously when Amasis, "the Drunkard", was

forced to depend on Greek forces to defend his Kingdom against the onslaught

of Persian imperial armies. The Persians first invaded Egypt in 525BC, initiating a period of foreign domination of the country, which lasted until 1952, when an Egyptian republic replaced the monarchy of King Farouk. The conquering Persians established the Twenty-Seventh Dynasty (525-404BC), which ruled Egypt with an iron hand. The Persians first invaded Egypt in 525BC,

initiating a period of foreign domination of the country, which lasted until

1952, when an Egyptian republic replaced the monarchy of King Farouk. The

conquering Persians established the Twenty-Seventh Dynasty (525-404BC),

which ruled Egypt with an iron hand.

|

|

|

The Persians, under the emperors Cambyses and

Darius, completed a canal connecting the Nile with the Red Sea, which had

been started by the Twenty-Sixth Dynasty king Necho II. They also

constructed temples and a new city on the site of what is now called Old

Cairo. This was called Babylon in Egypt.

The harshness of Persian rule resulted in

revolts against the Persian satraps Xerxes and Artaxerxes, which led to the

Twenty-Eighth dynasty of the Egyptian ruler Amyrtaeus and his successors.

The Egyptian kings of succeeding dynasties were under continual attack by

Persians until Artaxerxes III overthrew the Thirtieth and final Paranoiac

dynasty, remaining under Persian domination until the arrival of Alexander

the Great in 332BC. |

|

Greek Rule (332-30BC)

After centuries of upheaval and foreign incursions,

Egypt was in disarray when Alexander established his own Paranoiac rule,

reorganizing the country's government, founding a new capital city of Alexandria

and validating the religion of the pharaohs.

Upon his death in 323BC, the empire of Alexandria

was divided among his Macedonian generals. Ptolemy I thus established the

Ptolemaic Dynasty, which ruled Egypt for three centuries. Under the Ptolemys

Greek became the official language of Egypt and Hellenistic culture and ideas

were introduced and synthesized with indigenous Egyptian theology, art,

architecture and technology. The Ptolemy's synthesis of religious ideas resulted

in the construction of the temples of Edfu and Kom Ombo, among other sacred

structures. Alexandria became a great capital, housing one of history's greatest

libraries.

Gradually Ptolemaic rule was subverted by internal

power struggles and foreign intervention. The Romans made inroads into Ptolemaic

Egypt, supporting various rulers and factions until attaining total control over

the country when Julius Caesar's armies attacked Alexandria.

Queen Cleopatra VII was the last of the Ptolemaic

rulers who reigned under the protection of the Caesar with whom she had a son.

With the assassination of Caesar, Mark Antony arrived in Egypt and fell in love

with Cleopatra, living with her for 10 years and helping Egypt retain its

independence. The fleets of Octavian Caesar destroyed the Egyptian navy in the

battle of Actium, driving Antony and Cleopatra to suicide and Egypt became a

province of the Roman Empire.

Roman and Byzantine Rule

(30BC-AD638)

Octavian Caesar became the first Roman ruler of

Egypt, reigning as the Emperor Augustus. Egypt became the granary of the Roman

Empire and remained stable for about 30 years. The Romans, like their Greek

predecessors, synthesized many Egyptian beliefs with their own, building temples

at Dendara and Esna and Tranjan's kiosk at Philae. Hellenism remained a dominant

cultural force and Alexandria continued to be a centre of Greek learning.

The Christian era began in Egypt with the

spectacular biblical Flight of the Holy Family from Palestine. To this day

shrines and churches mark the stages of the journey of Mary, Joseph and their

infant Jesus. According to Coptic tradition, it was not until the arrival of

Saint Mark that Christianity was established in Egypt during the reign of Nero.

Saint Mark began preaching the gospel in about AD40 and established the

Patriarchate of Alexandria in AD61.

The Egyptian Coptic Church expanded over three

centuries in spite of Roman persecution of Christian converts throughout the

Empire. In AD202 the Roman authorities, continuing for nearly a century,

initiated persecutions against Copts. In AD284, during the reign of the Emperor

Diocletian, a bloody massacre of Coptic Christians took place from which the

church has dated its calendar. Christianity was legalized and adopted as the

official religion of the Roman Empire by the Emperor Constantine.

By the 3rd century AD the Roman Empire was in

decline as a result of internal strife, famine and war, finally splitting into

eastern and western empires. The Eastern Empire based in Constantinople became

known as the Byzantine Empire. The Western Empire remained centered in Rome. The

legalization of Christianity did not stop Roman persecution of the Coptic

Christians because the Byzantine church was based upon fundamentally different

beliefs than those of the Coptic Christian church which had adopted a

Monophysite belief in the total divinity of Christ, as opposed to the Byzantine

belief that Christ was both human and divine. The schism between the Byzantine

and Coptic churches was never closed.

The Copts were formally excommunicated from the

Orthodox Church at the Council of Chalcedon in AD451 and established their own

Patriarchate at Alexandria. The fifth century was also a time when monasticism

emerged and the Coptic monasteries of Saint Catherine, Saint Paul and Saint

Anthony were established as well as those at Wadi Natrun and Sohaag.

Apart from this doctrinal upheaval, the Byzantine rule over Egypt remained relatively stable until the coming of Islam.

The Early Islamic Period

(640-969)

Under the first Khalif of Islam Abu Bakr As-Siddiq,

the Prophet Muhammad's closest companion, the Muslim armies vanquished the

Byzantines in AD636. They advanced toward Egypt under the command of Amr Ibn

Al-As, one of the companions of the Prophet.

The Muslims laid siege to Babylon-in-Egypt, which

surrendered. They then took Heliopolis and in AD642 the Byzantine imperial

capital of Alexandria. Amr Ibn Al-As established Fustat north of

Babylon-in-Egypt as his military headquarters and seat of government and the

Egyptians swiftly embraced the new religion of Islam.

Egypt became part of an expanding empire that was

soon to stretch from Spain to Central Asia. The Umayyad Dynasty ruled Egypt from

Damascus until the Abbassids took control of the Khalifate and shifted the

political capital of Islam to Baghdad.

Ahmad Ibn Tulun who had been sent by the Abbassid

Khalif Al-Mu'taz to govern Egypt in AD868, declared Egypt an independent state

and successfully defended his new domain against the Abbassid armies sent to

unseat him. His dynasty ruled Egypt for 37 years. Ibn Tulun built Al-Qitai, a

new capital centered on a vast central mosque, the courtyard of which could

accommodate his entire army and their horses. But Tulunid rule was quickly ended

by the Abbassids, who retained direct control over Egypt until Mohammed Ibn

Tughj was appointed governor over the province and granted the title Ikhshid,

allowing him to rule independently of khalifa's controls.

The Ikhshidid Dynasty ruled from AD935-969 when Shi’a Fatimia armies from Tunisia invaded Egypt.

|

The Fatimia Period

(969-1171)

The Fatimid Dynasty traced their lineage from

the Prophet's daughter Fatima Zahra and her husband Ali Ibn Abu Talib. They

embraced Shi'a doctrines which rejected the legitimacy of the first three

Khalifs of Islam, Abu Bakr, Omar and Othman, who they claimed to be usurpers

of Ali's right to succeed the Prophet in leading Islam.

At first the Shi'a, or Partisans of Ali, were loyal members of the Muslim umma who simply disagreed with the political decision to bypass Ali. However Umayyad machinations which lead to the assassination and martyrdom of Ali and his sons Hassan and Hussein, hardened Shi'a attitudes and led to a religious schism with metaphysical overtones, which has persisted to this day. The Fatimids had separated themselves from

the Sunni Khalifate and set up their own western khalifate, which, with

their conquest of Egypt in AD969 extended across North Africa. The Fatimids

established their imperial capital within the walls of a newly built

imperial city called Al Qahira (Cairo), meaning "The Triumphant". Within the

walls of the city were lavish palaces and the Mosque of Al Azhar and its

University, which is now the world's oldest existing institution of

learning.

|

|

Egypt flourished under the Fatimids who ruled

behind the walls of their imperial city, maintaining the mystery of distance

from their subjects. It was not until the reign of the demented Khalif Al-Hakim

that the Fatimid decline began.

Although beginning his rule beneficently, building

a splendid mosque between Bab Al-Futuh and Bab An-Nasr in Cairo, and emerging

from his palace to meet his subjects to get a better understanding of their

needs, Al-Hakim degenerated into a murderous despot. He executed anyone to whom

he took a disliking and ruled with insane caprice. When he became enamored

of staying up all night, he made sleeping at night and working during the day

punishable by death. He banned the making of women's shoes. He also banned the

consumption of molokhia, a vegetable resembling spinach, which is a staple in

the Egyptian diet. He supported the Byzantines against Roman Christians and

the destruction of the Holy Sepulcher in Jerusalem, which was a pretext for the

First Crusade.

His reign ended mysteriously when Al-Hakim rode his

favorite mule up into the Mokattam hills at night. The mule was found but

Al-Hakim had vanished. Although it is likely that bandits who roamed the

outskirts of the city murdered him, hiding out in the hills or in the City of

the Dead, his disappearance was mythologized by his more extreme Shi'a followers

who believed that he was divine and had ascended to a spiritual realm.

Curiously, this heretical sect gained adherents and became known as the Druse

who still has communities in Lebanon, Syria, Jordan and Israel. Although the

Druse are clearly neither Muslim (Shi'a or Muslim), Christian or Jew, their true

beliefs remain shrouded in mystery as only the Druse priesthood are privy to

their doctrines and ordinary adherents are kept in total ignorance until the age

of 40.

Fatimid rule continued over Egypt for another 150

years and the country continued to prosper. However their empire gradually

declined due to famine, internal troubles and external pressure from the Seljuk

sultans who captured Syria from the Fatimids, and the Christian crusading

armies, which conquered Fatimid Palestine and the Lebanon. To protect the

remainder of their diminishing empire, the Fatimids collaborated with the

Franks, an act which outraged the Seljuk Sultan Nurad'din who sent an expedition

to overthrow the Fatimids.

The Sultan deputized his general Shirkoh to repel the Fatimid and Frank armies and conquered Upper Egypt, sending his nephew Salah al-Din Al-Ayyubi to capture Alexandria, thus opening the way for the Ayyubid Dynasty.

Ayoubid Rule (1171-1250)

Salah al-Din Al-Ayyubi ("Saladin") assumed control

of Egypt upon the death of the last Fatimid Khalif in 1171.

When the Crusaders attacked Egypt, burning part of

Cairo, Salah al-Din fortified the city and built the Citadel. His reign was a

golden age for Egypt and Salah al-Din is revered as one of the greatest heroes

of Islam, for his humility, personal courage, brilliant military and

administrative mind and for defeating the Christian armies and treating the

vanquished with dignity.

Salah al-Din spent eight years of his 24-year reign

in Cairo during which time he established the Seljuk institution of the madrassa,

built hospitals and other infrastructure. Salah al-Din also introduced Mamlukes

(an Arabic word meaning "owned"), Turkic slaves from the Black Sea region who

had been raised as mercenary soldiers. Under Salah al-Din and his successors

the Mamlukes were given a measure of freedom to own land and raise families and

some rose to positions of power and influence.

Upon the death of Salah al-Din in 1193, his brother, al-Adil, succeeded him following a protracted succession dispute. Al-Adil died in Syria, upon hearing the news of the crusaders' seizure of the chain bridge (burj al-silsila) at Damietta in 1218. His son and Salah al-Din’s nephew, al-Kamil, who drove back the Fifth Crusade, succeeded him. His successor, Sultan Ayyub, increased the size of his Mamluke army and married a slave girl called Shagarat Ad-Durr (Tree of Pearls). When Ayyub died, his wife became the first woman to rule Egypt since Cleopatra. She was the last ruler of the Ayyubids. Prophetic injunctions against women rulers placed Shagarat Ad-Durr in an untenable position and the Abbassids forced her to take a husband. When her new husband, Aybak, planned to take a second wife, Shagarat Ad-Durr had him murdered. She was assassinated shortly after this and the Mamluke military commander Baybars assumed control, ushering in the Mamluke period.

The Mamluke Period

(1250-1517)

Baybars, one of the great Ayyubid commanders,

seized power in the aftermath of Shagarat Ad-Durr's murder but his heirs were

murdered by Qalawun, another Mamluke who established the Bahri Mamluke dynasty,

named after the Mamluke garrison along the Nile River (Bahr Al-Nil). During his

reign Sultan Qalawun became a great patron of architecture and constructed

mosques, fortresses and other buildings in Cairo. Qalawun also established

relations many foreign countries in Europe, Africa and Asia. Qalawun's son

and successor, Mohammed An-Nasir who reigned for nearly half a century, from

1294-1340, was also a great patron of architecture.

The Mamluke armies of Sultan Mohammed An-Nasir

shocked the seemingly unstoppable Mongol armies by defeating them on the Syrian

battlefield. The descendants of Mohammed An-Nasir were weak and the Turkish

Bahri Mamluke dynasty gradually lost control of the sultanate, which was seized

by the Circassian Mamluke Barquq who established the Burgi Mamluke dynasty,

named after the Mamluke garrison set beneath the Citadel In Cairo. Although

Sultan Mohammed An-Nasir had made a treaty with the Mongols, they remained on

the borders of Syria and Sultan Barquq campaigned against the Mongols to drive

them out of the Near East altogether.

Heavy taxation was levied to pay for these

campaigns, debilitating the economy of Egypt. Conditions were exacerbated by a

plague that swept through the country during the reign of Barquq's son Farag. It

was not until the reign of Sultan Barsbey that Egypt regain its power. Barsbey

recognized the rising power and potential threat of the Ottoman Turks and

established good relations with them. He also extended Mamluki trade.

Nevertheless, the Mamluke economy remained unstable for nearly a century until

the reign of Sultan Qait Bey, another great Mamluki builder, who constructed

mosques, madrassas and other buildings throughout the empire.

The 46th Mamluki sultan was Qansuh Al Ghuri who continued the Mamluki architectural tradition but saw his economy crash after European traders began using the Cape of Good Hope for their spice trade rather than trading through Cairo. To add insult to injury, the Ottomans attacked Mamluke Syria and Sultan Qansuh fell in battle in 1516. The following year Tuman was executed by the Ottomans, signaling the end of the Mamluke Empire and the beginning of Ottoman rule, but the Mamlukes remained a powerful force within Egypt throughout the Ottoman period and beyond.

Ottoman Rule (1517-1798)

Although the Ottoman Turks were brilliant military

strategists and developed a rich Islamic civilization, they were poor colonial

administrators. They ruled Egypt from Istanbul through Pashawat who were trained

in Istanbul. Their direct involvement in government rarely extended to more than

enforcing tax collection. Otherwise the Ottomans exercised minimal control over

their new province and relied on the Mamluke army whose ranks continued to

expand with mercenary slaves brought in from the Caucasus. This lack of concern

manifested in neglect and deterioration, which opened the way for the French

invasion of Egypt in 1798.

European conquest

(1798-1802)

The armies of Napoleon crushed the Mamlukes at

Imbaba and occupied Cairo. Napoleon's aim was to block British trade routes to

India and to establish a Franco phonic society in Egypt. He imposed a French

administrative system and implemented public works projects to clean up and

renovate the long-neglected country, clearing blocked canals, cleaning the

streets and building bridges. Napoleon claimed to have respect for Islam and the

Qur'an but the Egyptians did not believe him.

For all his attempts at "civilizing" the country,

Napoleon failed to win the respect or allegiance of his subjects. His quixotic

mission was doomed from the outset. Within a month of entering Egypt the

British, under Admiral Nelson, attacked and destroyed the French fleet moored at

Abu Qir Bay in Alexandria and the Ottoman sultan threatened war against the

French. Napoleon returned to France, leaving his armies behind. But his

commander, General Kléber, was assassinated, leaving the army to General Menou,

who claimed to have converted to Islam and declared Egypt, a French

protectorate. At this, the British occupied Alexandria and with the Ottomans

captured Damietta and Cairo, forcing the French to surrender.

The Napoleonic invasion of Egypt had profound

repercussions for the Arab and Muslim world, which continue to influence the

region's political and social development. This was the first European conquest

of a major Arab country in the history of Islam and it signaled the rapid

decline of Islam as a world political power. Although it could be said that the

Ottoman Empire was by this time already a spent force, the humiliation of

Napoleon's entry into Egypt was a devastating blow to pan-Islamic pride. It has

been said that contemporary Muslim fundamentalism traces its psychological

origins to this initial shattering defeat.

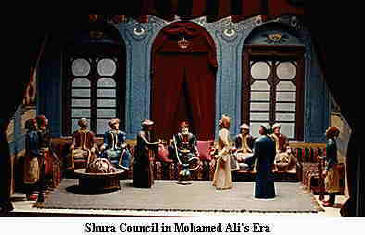

The Dynasty of Mohammed Ali

Pasha (1802-1892)

The French occupation destabilized Egypt and their defeat and withdrawal left the country vulnerable to an internal political struggle, which was won by Mohammed Ali, an Albanian lieutenant in the Ottoman army who, with Mamluke help, drove the British (temporarily) out of Egypt. The Ottomans elevate him to khedive or viceroy of Egypt.

In order to consolidate his power, the new khedive

realized he had to eradicate Mamluki power, which he did decisively and

spectacularly. After six years as ruler he invited 470 Mamluke soldiers to a

banquet at the Citadel. It was a trap. All were massacred and the Mamluke threat

was ended.

Although Mohammed Ali was nominally a representative of the Ottoman Sultan he was for all intents and purposes an absolute ruler.

|

He was dedicated to the modern development of

Egypt, building factories, railways and canals, bringing in European

architects and technicians to create a modern state.

Mohammed Ali was also an ambitious expansionist

whose armies extended his power over Syria, Sudan, Greece and the Arabian

Peninsula until by 1839 he controlled a large portion of the Ottoman Empire.

Throughout his reign, however, Mohammed Ali always kept up the pretence of

being a loyal representative of the Khalif. When it became clear that his

power was exceeding acceptable limits, the British intervened, forcing him

to relinquish some control to the Ottoman sultan. Mohammed Ali died in 1848

leaving his grandson Abbas to succeed him. Abbas opened Egypt to free trade,

closing schools and factories and effectively halting the moves towards

industrial development and economic self-sufficiency Mohammed Ali had set in

motion.

Said Pasha, the son and successor of Abbas, reversed his father's policies and actively set about developing the country's infrastructure and initiated the building of the Suez Canal, which was completed in 1869 by his successor the Khedive Ismail. Under his rule, industrial and civil infrastructure was further developed. More factories were built. A telegraph and postal system was established. Canals and bridges were constructed and the cotton industry, which had been introduced during the reign of Mohammed Ali, began to flourish as a result of the American Civil war, which prevented southern cotton production for the duration of the war. However, all this expansion had a price.

Ismail's modernization put Egypt heavily into debt and the end of the Civil

War and resumption of American cotton production caused a major recession in

Egypt's cotton industry. As a result of this economic crisis, Khedive Ismail

was forced to abdicate in 1879 and the British began to assume greater

control over the country. |

|

British Occupation

(1882-1952)

Ismail's son Tewfiq Pasha reformed the Egyptian

economy and relinquished financial control to the British who began to run the

government of the country. Egyptian nationalists, horrified at Tewfiq's

submission to the British, forced him to appoint their leader Ahmed Orabi as

Minister of War, but the European reaction was swift and violent. Alexandria was

shelled and Ismailiyya occupied. Orabi's army was defeated at Tel El Kabir and

the British reinstalled Tewfiq as a puppet. Orabi was driven into exile and

Mustafa Kamil became the leader of the nationalist movement.

British influence over Egypt continued to increase.

The country became an economic colony, totally dependent upon the import of

British manufactured goods and the export of its raw cotton.

The outbreak f the World War I brought Egypt

formally into the British Empire as a Protectorate when the Ottoman Sultan

declared his support for the Germans against the allies. During the war Fouad,

the sixth son of Khedive Ismail, had become Khedive of Egypt but his authority

was to be constantly challenged by Egyptian nationalists who fed on the popular

resentment of foreign domination.

Sa'ad Zaghloul was the leader of the nationalist

movement during and after the war and in 1918 he formally presented the British

High Commissioner with a demand for complete autonomy, which was rejected out of

hand. Zaghloul's eventual arrest and deportation to Malta resulted in widespread

anti-British riots, forcing the British to back down.

| In 1922 the

British ended the protectorate and recognized Egypt's independence, while

maintaining control over the essential government institutions and the Suez

Canal. Fouad was proclaimed King of Egypt in March of the same year.

A triangular power struggle between the British, the King and the nationalist Wafd party, which had the support of the population, characterized the years that followed.

Farouk, the son of King Fouad, ascended the

Egyptian throne in 1935. In the beginning, the reign of King Farouk was

greeted with enthusiasm by both the Wafd party and by the rapidly growing

Muslim Brotherhood. Farouk was, amazingly, the first Egyptian ruler of the

descendants of Mohammed Ali Pasha to speak fluent Arabic. Turkish had

been the court language of all his predecessors. Moreover, Farouk seemed to

have nationalist sympathies. The young ruler was, unfortunately, too

weak-willed to defy the British. Within a year he had signed the

Anglo-Egyptian Treaty, which gave British forces the right to remain in the

Suez Canal Zone while ostensibly ending the British occupation of Egypt.

|

|

With the outbreak of World War II the Wafd Party

threw its support behind the allies on the understanding that Egypt would gain

full independence once the war was over. But the hatred of British rule was so

intense by this time that clandestine support for the Germans existed in

nationalist factions like the Muslim Brotherhood.

Egypt became a major strategic asset and base of

operations during World War II. Cairo and Alexandria were filled with soldiers,

spies, political exiles and government leaders. The decisive battle in the North

African campaign was the Battle of El-Alamein in the desert outside Alexandria.

General Montgomery's Eighth Army drove back Rommel's Afrika (Africa) Korps and

the allies swept across North Africa to victory.

With allied victory and the end of the war the Wafd

party called for the immediate evacuation of British troops from Egypt. The

British were slow to respond and Egyptian resentment exploded in anti-British

riots and strikes, instigated by the highly organized Muslim Brotherhood under

the leadership of Hassan Al-Banna which had grown in power and influence during

the war years.

It had always been the Muslim Brotherhood position

that the war between the allies and the axis had nothing to do with Egypt or

Muslims. The leadership of the Muslim Brotherhood refrained from open opposition

to Egyptian support for the allies during the war years but lashed out at the

British presence after the war. Under joint pressure from the Brotherhood and

the Wafd, British troops were evacuated from Alexandria and the Canal Zone in

1947.

The following year the Arab world suffered a

shattering blow when the smaller Israeli army ignominiously defeated a joint

Arab invasion of the newly declared state of Israel. Ashamed and appalled by the

decadence and gross incompetence of their leaders, a group of idealistic young

Egyptian officers were to emerge as leaders of a revolution, which would alter

the course of modern Arab history.

When parliamentary elections were held in 1952 the Wafd Party won the majority of seats and Nahas Pasha as prime minister repealed the 1936 treaty, which gave Britain the right to control the Suez Canal. King Farouk dismissed the Prime Minister, igniting anti-British riots, which were put down by the army.

| This event compelled a secret

group of army officers, which became known as the Free Officers, to stage a

coup d'etat and seize control of the government. King Farouk was forced to

abdicate and General Naguib -- as the most senior officer, the nominal

leader of the group -- became Prime Minister and commander of the armed

forces.

In reality a nine-man Revolutionary Command

Council (RCC) led by Colonel Gamal Abd Al-Nasser ruled Egypt and ruled

decisively. The monarchy was abolished, all political parties (including the

Wafd) were banned and the Constitution was nullified.

|

|

In 1953 the Egyptian Arab Republic was declared. In the beginning, the rule of the Revolutionary Command Council seemed benign and heroic. Their coup had been bloodless, their reforms popular. But the RCC became increasingly radical and when the older Naguib tried to exert some control over the younger officers he was placed under house arrest and removed from power in 1954. Abd Al-Nasser became acting head of state and in 1956 officially assumed the presidency of the republic.

Nasserist rule (1956-1970)

| Gamal Abd-Al

Nasser was a charismatic, ruthless and brilliant political leader who

transformed pan-Arab politics and left a troubled legacy to Egypt and the

Arab world. There is little doubt that Nasser was a sincere Egyptian patriot

who wanted to improve the lot of his people. But he was also a man utterly

committed to the retention of power at any cost, which quickly evolved

into a harsh, repressive socialist-style dictatorship. Those involved in

political opposition were persecuted, driven underground, imprisoned,

tortured, exiled or executed.

Gamal Abd-Al Nasser was a charismatic,

ruthless and brilliant political leader who transformed pan-Arab politics

and left a troubled legacy to Egypt and the Arab world. There is little

doubt that Nasser was a sincere Egyptian patriot who wanted to improve the

lot of his people. But he was also a man utterly committed to the retention

of power at any cost, which quickly evolved into a harsh, repressive

socialist-style dictatorship. Those involved in political opposition were

persecuted, driven underground, imprisoned, tortured, exiled or executed.

|

|

The Muslim Brotherhood, which had initially

supported the 1952 revolution, was outlawed and thousands of its members were

imprisoned. The Wafd suffered a similar fate. Journalists who disagreed with the

regime were silenced. A totalitarian pall fell over Egypt during the Nasser

years. Industry and then private property was nationalized.

Ironically, as he was rounding up the opposition,

Abd-Al Nasser achieved unprecedented popularity throughout the Arab world. He

was admired for his rousing support of Arab Nationalism; his domestic social

programs(which, for the first time in Egypt's history, sought to better the lot

of the peasant majority); his dramatic nationalization of the Suez Canal; and

also because of Egypt's heroic stand against the British invasion.

However Nasser's vehement opposition to Israel and

his outspoken criticism of the West lost him US and European support for the

building of the Aswan High Dam, forcing the Egyptian president to turn to the

Soviets for aid. The need for capital to build the High Dam is cited as one of

the reasons for nationalizing the Suez Canal.

Whatever Nasser's initial intentions, the Suez

Crisis propelled him to the forefront of the Arab Nationalist movement. Pan Arab

unity became the overriding theme of the Arab world from the late 1950s up to

1967 and Nasser became its chief advocate and spokesman. The most dramatic

display of Pan-Arabism took place in 1958 when Egypt united with Syria to form a

single country, the United Arab Republic. But Nasser, for all his oratory, was

essentially an Egyptian nationalist. The practical interests of the two

countries never meshed and the union came to nothing.

But Nasser's revolutionary pan-Arabism was not all

talk. Egypt entered the Yemeni civil war against the monarchy on the side of

leftist guerrillas, further alienating the west and Saudi Arabia. At the same

time he strengthened Egypt's ties to the Soviet Union, relying on the communist

bloc for technical and military assistance to build an army to fight the US

supported Israeli army. Nasser also supported the formation of the Palestine

Liberation Organization, further alienating him from the West.

Nasser's relations with the West were complex. He

knew that he could never develop Egypt without large infusions of foreign aid

and he knew that the West was the most reliable source of this aid. Yet he came

to discover that the more anti-Western his stance appeared to be, the more

foreign aid he was offered by western countries to buy his moderation. When at

one point in his regime he became more conciliatory to the west, his foreign aid

dropped dramatically. As a founding-leader of the Non-aligned movement Nasser

could have it both ways. Along with India's Nehru and Indonesia's Sukarno, Gamal

Abd-Al Nasser became a major international power broker in the politics of the

developing world.

Nasser's pan-Arab politics of the period tend to

overshadow the achievements of his regime. Land reform was put into effect,

breaking up the large feudal estates into smaller parcels of land and

redistributing land to the fellaheen who for millennia had been an underclass of

serfs. When the Aswan High Dam was completed, arable land in the Nile Valley

increased by 15%. Nasser also built the country's industrial base, powered by

electricity generated from the High Dam.

Prior to the revolution, Egypt had been an elitist

society with few if any state-sponsored benefits to the large majority of the

population. The new government established extensive free educational programs

for both boys and girls and developed the country's medical infrastructure.

The country had to pay a heavy price for much of

this development. Political repression and censorship increased. The educated

classes and political elite who could have contributed to the building of the

country were disenfranchised and persecuted. An under-educated socialist

bureaucracy which provided Nasser with his power base, but which was grossly

incompetent, setting the lowest possible standards for the administration of a

great country, replaced them. Economic stagnation and industrial and

agricultural inefficiency subverted real development. Rhetoric had replaced

reality.

The Six-Day War in 1967 marked the end of Nasser's

Pan-Arab dream. The Arab world's ignominious defeat by Israel ended in the

Israeli occupation of Syria's Golan Heights, the Gaza Strip and the West Bank in

Palestine and, most painfully for Egypt, the Sinai. However, the greatest

symbolic humiliation for the Arabs was the fall of Jerusalem. The bombastic

rhetoric of Arab leaders now seemed like so much hot air. Hatred of Israel and

its chief supporter, the United States, reached a pinnacle.

The defeat of the Egyptian army and the loss of Sinai would have destroyed the political career of an Arab leader of lesser stature and indeed, Abd-Al Nasser offered to resign as president. Such was his extraordinary popularity that the Egyptian people staged massive spontaneous demonstrations in support of the president and he remained in power. His death in 1970 of a heart attack sent shock waves throughout the Arab world. In a stunning display of emotion, millions of Egyptians followed his funeral procession through the streets of Cairo.

The rule of Sadat (1970-1981)

Anwar Saddat had been one of the original Free

Officers and served as Nasser's vice-president and chosen successor, but he had

never been taken seriously until he assumed control of the government. Saddat

began to systematically reverse the failed socialist policies of his

predecessor, ultimately expelling the Soviets and reforming the economy. But it

was Saddat's surprise attack against Israeli forces in the Sinai on the Jewish

holiday of Yom Kippur during the Muslim holy month of Ramadan on October 6,

1973, which gave Sadat the credibility, which earned the respect of his

countrymen. The October War shattered the image of Israeli invincibility, which

had persisted since the Six Day War and gave the Arab world a tremendous

psychological boost. Although the war turned against the Arabs and ended in a

stalemate, Sadat emerged as a hero.

Sadat then set about liberalizing the Egyptian

system. Political prisoners were granted amnesty, censorship of the press was

lifted and political parties were allowed. Sadat also made a show of reversing

the harsh secularism, which was beginning to alienate the still traditionally

religious middle classes by strongly identifying himself as a devout Muslim. At

the same time, he instituted the Infitah, or Open Door policy, encouraging

foreign investment and the development of the private sector. Gulf Arab

investments began to flow into the country and international investment and

foreign aid increased.

Still, the specter of another debilitating war with

Israel loomed. After years of socialist privation and militarism the Egyptian

people had had enough. Although there were still echoes of pan-Arabism, the

booming oil-producing Gulf economies had undergone a shift in attitude. At the

same time, Egypt was facing pressure from the International Monetary Fund to

remove the food subsidies, which were sapping the country's financial reserves.

Sadat knew that this would undermine his political

power so, instead of graduating the removal of subsidies, he did it in a single

day at the beginning of 1977, and causing prices to double suddenly and igniting

what have been called the food riots. It was a brilliant ploy, which caused the

IMF to back down and reschedule Egypt's loans and the US to increase its foreign

aid to the country. Food subsidies were immediately reinstated.

Sadat made his most dramatic and controversial

political move later the same year. On November 19, 1977 Sadat suddenly traveled

to Jerusalem with overtures of peace to Israel. On a global level the move was

brilliant, catapulting Sadat to the front ranks of international diplomacy.

Sadat became the darling of the west and gave the Arab world a new image of

moderation.

On a domestic and regional level, Saddat’s peace

initiative was to outrage the Arab world and alienate the president from many of

his people. Never as charismatic as his predecessor, Sadat was perceived as a

traitor, toadying to western interests. Egypt was the first Arab state to

recognize Israel's right to exist and the subsequent Camp David agreements,

which won Sadat and Israeli Prime Minister Menachem Begin the Nobel Peace Prize,

further isolated Egypt from the rest of the Arab world. The Arab League

relocated from Cairo to Tunis and many Arab countries severed diplomatic and

trade relations.

Saddat’s cultivation of the West, which was

initially greeted with enthusiasm by most Egyptians, began to backfire after the

peace initiative. Economic liberalization, which brought wealth to the upper and

middle classes, brought inflation to the country and increased the poverty of

the lower classes.

Saddat’s support for Islam also began to backfire as groups like the Muslim Brotherhood gained wider support and became more vocal in their criticism of government economic policies and the Camp David agreements, which were portrayed as a sell out to the Zionists. Militant fundamentalist groups throughout the Arab world and in Egypt began to call for Saddat’s overthrow or assassination. After relaxing government repression Sadat resorted to wide-scale arrests and the western media who had coddled him since Camp David, suddenly turned on the president.

In October 1981 Sadat was assassinated at a military parade. He had become so isolated from his people by this time that his death and funeral elicited little reaction from a people that had poured into the streets in grief when his predecessor had died.

The rule of Mubarak

(1981-present)

| Mohammed

Hosni Mubarak had been Sadat's vice-president since 1974 and, like Sadat,

seemed singularly unimpressive prior to assuming the presidency. At first he

continued Sadat's policies but with less flamboyance and more domestic

sensitivity. He allowed the publication of Islamic newspapers and downplayed

the Israeli connection. At the same time, he accelerated the process of

privatization and developed Egypt's tourist infrastructure, which enhanced

its lucrative tourist industry.

More impressively, he managed to resume

diplomatic and trade relations with moderate Arab countries while

maintaining the treaty with Israel. By the end of the 1980s Egypt was once

again playing a leading role in Arab politics. Egypt's vital role in support

of Saudi Arabia and Kuwait in the Gulf War combined with death of

socialist-communist influence in the Arab world returned the country to the

centre of Middle Eastern politics.

|

|

However, Egypt's domestic situation is far from

stable. The country's economic reforms and infrastructure development cannot

keep pace with the population explosion and inflation. Extremist Muslim groups

launched a campaign of terrorism against foreigners, which paralyzed the

government and damaged tourism between 1992 and the beginning of 1994. But

security forces broke the main terrorist groups in Cairo and Upper Egypt and the

summer of 1994 experienced a spectacular revival of tourism, particularly from

Saudi Arabia and the Gulf States.

Although most terrorist cadres have been imprisoned

and many have been sentenced to death, the threat to Egypt's stability remains,

as Islamic fundamentalism becomes more deeply rooted in Arab societies.

President Hosni Mubarak was sworn in for a further six-year term in office on 5 October 1999. Mubarak, the only presidential nominee, won nearly 94 percent of the votes in a popular referendum on September 26.